Choices that will shape what comes next

Restoring macroeconomic stability without suffocating growth is key

Published :

Updated :

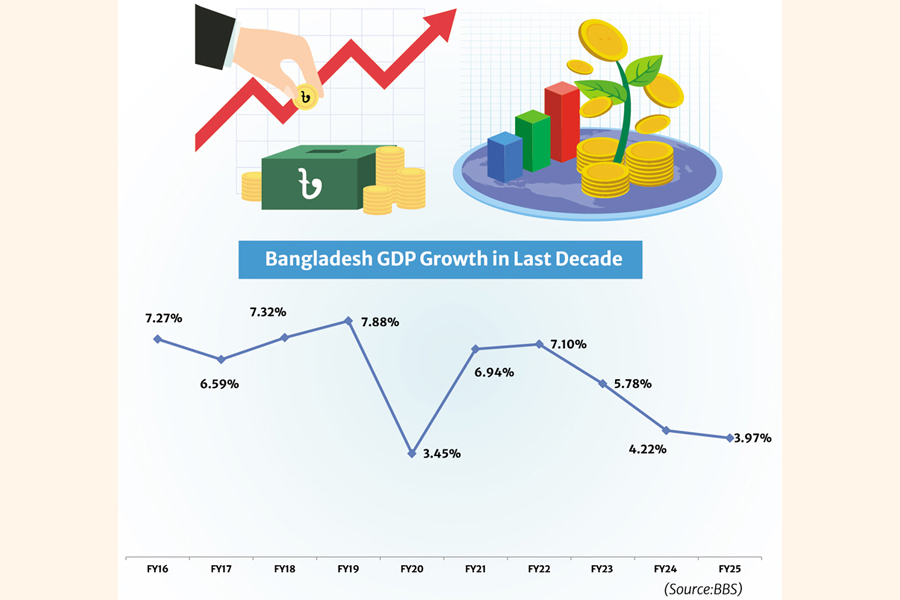

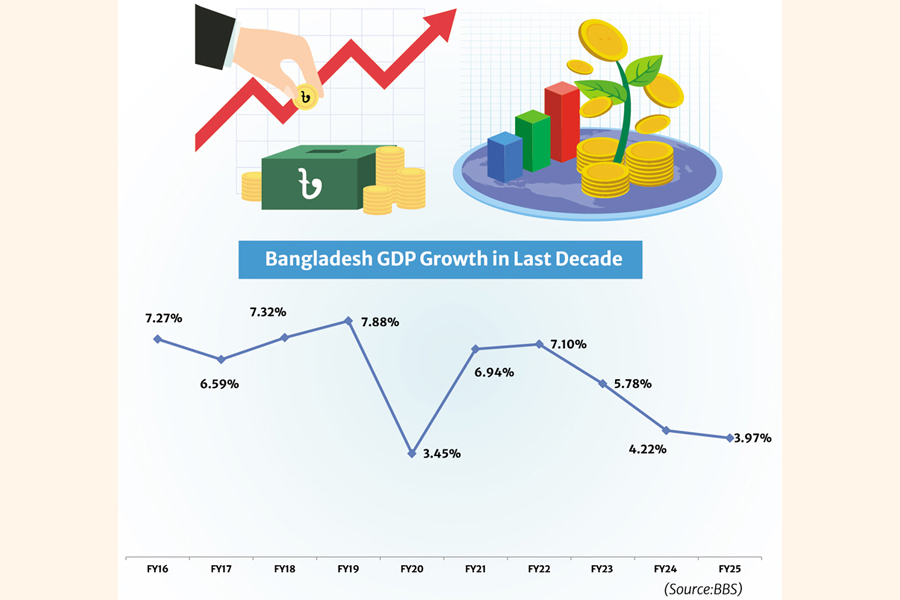

Bangladesh’s economy is showing signs of stabilisation. Foreign exchange reserves have improved, import compression has eased immediate pressure, and the worst phase of panic in foreign exchange markets appears to have passed. Yet that surface calm hides a more uncomfortable reality. Growth has slowed in a way that feels structural, not temporary. Inflation remains strikingly stubborn, especially in the non-food basket that shapes daily urban life. Investor confidence is fragile, not only because of macro numbers, but because rules feel unpredictable and enforcement feels uneven. And beneath all this, long-standing weaknesses remain unresolved: a narrow export base, weak revenue capacity, a strained banking system, and an economy where too many workers remain informal, low-skilled, and under-protected.

Many of these pressures did not begin with the political upheaval of 2024. They were building earlier. Private investment had already been losing momentum. Productivity growth had started to decelerate. The export model was becoming more concentrated rather than more diversified. The shocks of recent years simply exposed what had been accumulating quietly: a development model that delivered growth for a long time, but did not build enough resilience into its institutions, its financial system, or its capacity to create good jobs outside a few headline sectors.

Now the timeline tightens. With the Least Developed Country (LDC) graduation in November 2026 approaching, the transition is no longer a distant policy debate. It is a live economic constraint. Preferential market access will gradually erode. Compliance expectations will rise. Competition will sharpen. That does not mean collapse is inevitable. But it does mean the margin for policy mistakes becomes smaller. Small inefficiencies that were once absorbed through preferences will turn into lost orders, lost investment decisions, and lost jobs.

Inflation is the most immediate burden for households. Even when headline figures soften, essential non-food costs continue to creep upward: housing, transport, healthcare, and education. Real incomes have been squeezed because wage adjustments have been slower than price increases. Inflation, in other words, has become a persistent tax on living standards, and that tax falls hardest on those who cannot hedge.

Policy responses have been incomplete. Monetary tightening came late, and it has been unevenly transmitted through a banking system carrying weak balance sheets. Liquidity support for troubled institutions has sometimes continued even as high interest rates raise borrowing costs for productive firms. The result can be a toxic mix: high rates and sticky inflation, where investment is discouraged but price stability does not arrive in full.

The financial sector remains under severe strain. Non-performing loans (NPLs) have climbed, asset quality has deteriorated, and capital buffers are thin. When banks are weak, they do two things that hurt growth. They ration credit to productive firms, especially smaller ones that do not have political connections. And they raise borrowing costs, because risk and uncertainty are priced in. This is one reason employment and production have struggled to regain momentum. Temporary solutions like mergers, ad hoc rescheduling, or periodic liquidity injections can reduce headline stress, but they do not address the governance failures that caused the problem.

Investment has also been weighed down by uncertainty and by the rising informal costs of doing business. Supply disruptions, inconsistent enforcement, growing law and order concerns, and a broader climate of unpredictability have heightened risks for firms. In this environment, even investors with capital hesitate to commit to long-term projects. They wait, and waiting becomes rational. That is why the political transition is economically decisive. A credible transition that restores predictability and enforcement can unlock investment without any miracle policy package. Without it, stagnation can deepen, regardless of how many stimulus measures are announced.

The next government will therefore have to do more than stabilise. It will need to describe a development strategy that is purposeful rather than reactive, one that creates jobs at scale, raises productivity, broadens inclusion, and prepares the economy to compete without special treatment. Achieving this requires sound policy, yes. But it also requires institutional credibility and political discipline. Without these, even good policies will fail in practice.

Against the backdrop, the sections that follow outline key economic priorities for the next government. They draw on recent reform debates and on the concerns voiced across business, policy, and research circles, but they are reorganised into a single integrated narrative focused on action. Diagnosis matters. But at this stage, what matters more is what to do differently, and how to do it in a way that actually delivers.

Restoring Macroeconomic Stability without Suffocating Growth: The first priority is to lock in macroeconomic stability, while avoiding the trap of prolonged stagnation. Stability achieved through collapsing investment, falling real incomes, and shrinking public services is neither socially sustainable nor politically durable. The goal should be a stable macro environment that is compatible with growth, not a narrow focus on a few headline indicators that look good on paper but feel harsh in daily life.

Inflation: a balanced strategy, not a single lever. Inflation remains the most visible concern for households. Food inflation has eased at times, but non-food inflation is still stubbornly high. That tells us something important. Inflation in Bangladesh today is not purely a demand-side phenomenon. It reflects supply bottlenecks, weak market supervision, energy price distortions, logistical inefficiency, and in some cases outright manipulation in critical commodity markets.

This is why relying almost entirely on tight monetary policy is both risky and insufficient. High rates drive up borrowing costs for producers. They discourage private investment. They squeeze working capital for SMEs, which are often already fragile. Yet high rates do not fix the structural causes of inflation. They cannot repair food supply disruptions, reduce transport costs, or eliminate market power that allows a few players to influence prices.

The next government will need a more balanced anti-inflation strategy. Monetary restraint is still necessary, particularly to prevent inflation from becoming entrenched. But it must be accompanied by targeted supply-side interventions that reduce price volatility at its source. Better storage and cold chain capacity, improved logistics, and more reliable distribution networks matter. Strategic reserves for fertiliser, diesel, and key staples can dampen shocks. Faster and more predictable import approvals during shortages can reduce panic. Market monitoring must move from occasional raids to consistent oversight supported by data, clear rules, and credible enforcement.

There is also a political economy dimension here. When citizens believe markets are rigged, inflation becomes not only a macro issue but a legitimacy issue. That is why transparency in price data, stronger consumer protection, and credible action against collusion are not side issues. They are part of stabilisation.

Exchange rate policy: realism, predictability, and fewer distortions. Exchange rate management is another sensitive area. Recent experience shows that artificially defending the taka is costly and unsustainable. It drains reserves, creates incentives for informal transfers, and produces a confusing multiple-rate environment that undermines trust. A more realistic, market-aligned regime, one that can move both ways rather than only depreciate in steps, can reduce speculative pressure and improve confidence.

The improvement in remittance inflows through formal channels in periods when incentives align with reality offers a hint of what is possible. When the gap between official and informal channels shrinks, formal inflows rise. This is not a moral lesson. It is an incentive lesson. A credible exchange rate regime also helps exporters plan, importers price inputs, and investors assess returns. Uncertainty is a tax on decision-making. Predictability is a stimulus.

A “first 100 days” macro package: credibility before complexity. Stabilisation is not only about what policies are adopted. It is also about how quickly the government signals seriousness, coherence, and discipline. The early months matter because they set expectations. A practical approach is to announce a “first 100 days” macro and governance package focused on credibility: clearer monetary fiscal coordination, transparent exchange rate management, visible market monitoring reforms, and immediate steps to reduce policy arbitrariness.

This does not mean populist price controls. It means predictable rules, better enforcement, and targeted protection for vulnerable groups while inflation remains high. Early credibility can lower risk premiums, reduce panic behaviour, and create space for deeper reforms later.

Protecting growth while stabilising. Crucially, stability must not become an excuse for neglecting growth. Private investment must recover if GDP growth is to move beyond the current low trajectory. That recovery will depend less on macro numbers alone and more on confidence: confidence that policies are predictable, contracts are enforceable, and informal costs will not spiral unexpectedly.

The government should also recognise that growth today is constrained by both demand and supply. When inflation squeezes households, consumption weakens. When banks are weak, credit weakens. When energy supply is unreliable, production weakens. Stabilisation, therefore, must be comprehensive. Otherwise, the economy drifts into a low-growth equilibrium that is stable on paper but stagnant in reality.

Reviving Investment and Production – From Narrow Engines to a Broader Base: Bangladesh’s growth story over the last three decades was driven largely by a few engines: ready-made garments, remittances, and large-scale infrastructure investment. This model delivered early gains. But its limitations are now increasingly visible. The question is not whether those engines remain important. They do. The question is whether the economy can build new engines alongside them, and whether it can fix the bottlenecks that prevent investment from translating into productive expansion.

The investment climate: uncertainty, informal costs, and rule of law. Investment decisions depend on expected returns, but they also depend on predictability. When enforcement is inconsistent, when law and order concerns rise, and when informal costs become harder to anticipate, firms delay expansion. Even domestic firms behave like foreign investors in such a climate. They keep money liquid, they shorten planning horizons, and they avoid projects that require long payback periods.

This is why restoring the rule of law is an economic policy, not only a political one. A predictable environment reduces risk premiums. It lowers the cost of capital. It makes policy announcements credible. The next government must treat business confidence as an asset. And like any asset, it can be built or destroyed quickly. Restoring confidence requires visible improvements in enforcement, dispute resolution, and the credibility of regulatory agencies.

Export concentration and the diversification imperative. Export concentration remains extreme. More than four-fifths of merchandise exports still come from garments. This leaves the economy exposed to shifts in global demand, changes in trade rules, labour and environmental compliance pressures, and technological automation. LDC graduation will intensify these risks as preferential market access gradually erodes.

Diversification, therefore, is not a slogan. It is economic insurance. The challenge is to do it in a disciplined way. Bangladesh should focus on sectors where it already has a foothold and where scale-up is plausible within a decade. Spreading incentives thinly across too many priorities creates noise, not momentum.

Promising areas include agro processing, light engineering, pharmaceuticals, ICT and IT-enabled services, electronics assembly, medical supplies, and renewable energy components. These sectors share a common constraint: entrepreneurs exist, but coordinated support is weak. Access to finance is limited. Quality infrastructure is uneven. Standards and certification capacity are inadequate. Skills pipelines are thin. Market intelligence is fragmented.

Industrial policy that rewards performance, not connections. Industrial incentives must be redesigned to reward performance rather than connections. Assistance should be time-bound, transparent, and linked to measurable outcomes: export expansion, productivity increases, technology adoption, compliance improvement, or job creation. Support should be reviewed regularly and withdrawn if targets are not met.

This discipline matters for two reasons. First, it prevents public resources from entrenching inefficiency. Second, it signals to investors that the rules are credible. When incentives are opaque, investors assume rent seeking will dominate. When incentives are transparent and rule-based, investors plan for performance.

Regional industrial ecosystems: reducing congestion and imbalance. Geography matters. Industrial activity is concentrated around Dhaka and a few other hubs, creating congestion, high living costs, and regional imbalance. This concentration also increases vulnerability. When a city faces disruption, the entire production network suffers. The next government should prioritise regional industrial ecosystems. That means combining infrastructure, skills institutions, and SME clusters in selected districts, rather than scattering projects across the country without coordination. Well-functioning economic zones can support this strategy, but only if delays, land issues, and utility constraints are addressed decisively.

Economic zones should not be treated as real estate ventures. They should be treated as productivity platforms. If utilities are unreliable, if customs procedures remain slow, and if governance is weak, zones will not deliver industrial transformation.

Investment administration: from obstacle course to service delivery. Even after years of rhetoric about one-stop services, investors still face an obstacle course of approvals and unpredictable delays. This is not only a bureaucratic problem. It is a competitiveness problem.

The next government should push hard on practical reforms: transparent deadlines, digital tracking, silent approval processes, and credible appeals mechanisms. Agencies must be evaluated on service delivery outcomes, not on how many meetings they hold. A single digital platform can help, but only if it is backed by accountability across agencies. Otherwise, digitisation becomes a new layer on top of old delays.

SMEs and vendor networks: the missing middle. Bangladesh’s production ecosystem is weakened by the fragility of SMEs. Large firms depend on vendor networks for inputs, services, and innovation. When SMEs cannot access credit, cannot get predictable utilities, and cannot operate in a secure environment, supply chains remain shallow, and import dependence remains high.

Supporting SMEs is not charity. It is an industrial strategy. Credit guarantee schemes, transparent refinancing windows, and simplified compliance procedures can help. But the deeper need is governance: fair lending, predictable regulation, and reduced harassment.

Innovation, research, and economic sophistication. Bangladesh’s competitiveness problem is increasingly about sophistication. Competing only on low wages is not a sustainable strategy in a world of automation, compliance requirements, and fast-moving supply chains. Productivity growth will depend on innovation, adoption of technology, and investment in research and development.

The next government should treat innovation policy as part of industrial policy. That means incentives for firms to invest in technology upgrading, stronger linkages between universities and industry, and support for applied research in sectors where Bangladesh can build an advantage. Without this, diversification will remain shallow, and value chains will remain low. [To be continued]

Dr Selim Raihan is a Professor at the Department of Economics, University of Dhaka, and Executive Director at the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM).

selim.raihan@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.